Edwin Forrest - America's First Star

Guest Blogger: Andrew Terranova, Concierge, Sofitel Philadelphia

Related Posts:

- Buy Tickets for The Constitutional Walking Tour of Philadelphia – See 20+ Sites on a Primary Overview of Independence Park, including the Liberty Bell and Independence Hall

- The Grace Kelly Home

- Philadelphia Music Alliance's Walk of Fame

- Signers' Walk

- Avenue of the Arts

“The actor's popularity is evanescent; applauded today, forgotten tomorrow.”

– Edwin Forrest

Philadelphia boasts its fair share of famous actors born here: Grace Kelly, Tina Fey, Bradley Cooper, the Barrymores, etc. One monumental figure in American acting history towers above them all. Now nearly forgotten, Edwin Forrest (1806-1872) was a pioneer of the American theater. A brawny, powerful man, with a booming baritone voice, he had the power to enrapture audiences. He stood five feet, ten inches tall with a noticeably muscular build (he always favored roles which allowed him to display his massive arms and legs), that on stage made him appear like a giant.

America's First Star

Forrest was America’s “first star” at a time when British actors "ruled the boards" and an imposing tragedian who performed almost all of Shakespeare’s great roles in repertory and had a huge success as Spartacus. Drama critic William Winter described Forrest as "…a vast animal, bewildered by a grain of genius, who was personally an utterly selfish man, but as an actor, Forrest, at his best, was remarkable for iron repose, perfect precision of method, immense physical force, capacity for leonine banter, fiery ferocity and occasional felicity of elocution." "He had head tones that splintered rafters," rhapsodized the New York World. His voice was deep and husky according to others. "He soared above all the Hamlets of the day," wrote James Rees in 1827.

Forrest had a storied legacy in Philadelphia and never forgot his theatrical roots here in America’s birthplace. His fame in America was frenzied, adored by many, likely on par with Tom Cruise at the height of his film career. But fame didn’t come without your standard “E True Hollywood Story” scandals as with many celebrities. However, his scandal resulted in the deaths of dozens of people in the Astor Place Riots in New York City in 1849 (which I will discuss in this blog). Giving credit where it is due, Forrest was also a philanthropist who sponsored playwriting contests for American writers and even founded a retirement home for older actors.

Forrest was born in Philadelphia on March 9, 1806. The US Capital had moved to a new city on the Potomac River just over 5 years earlier, and Thomas Jefferson was President of the United States. The Philadelphia street just off Second and South where Edwin Forrest was born is now known, appropriately, as American Street.

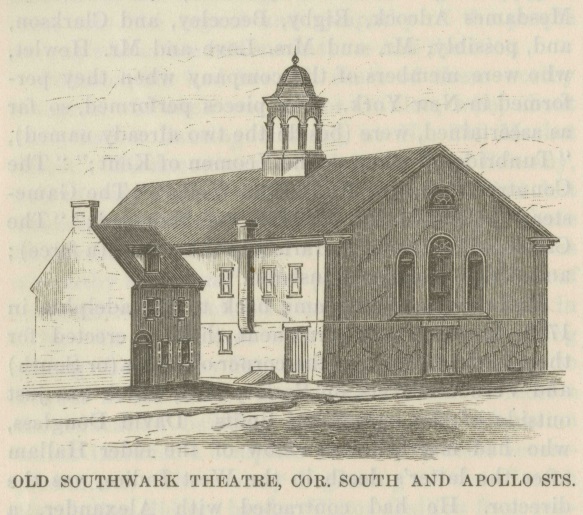

But in 1806, it was called George Street (named for George Washington). Edwin’s father was an immigrant from Scotland who worked as a clerk at Alexander Hamilton’s First Bank of the United States. His mother, Rebecca Lauman, came from an affluent German-American family. Edwin, or Ned, as he was called, got a job working with a ship chandler. He spent all of his spare time reading the works of Shakespeare and performing with his brother William and other neighborhood kids in a makeshift theater in a shed. All that practicing of Shakespeare paid off. In 1817, at the tender age of 11, Forrest was discovered by the manager of the Southwark Theater, which once stood at the current spot of South and Leithgow Streets, a few blocks from his home. Noting his lithe attractiveness at such a young age, the manager of the theatre cast him in the tiny, tiny, tiny role of Rosalia de Borgia in Rudolph; or The Robber of Calabria.

Thus, Forrest's first performance was in a female role, which was very common at the time. From the moment he first hit the boards as an adolescent, a star was born! In 1819, Forrest’s father died of consumption. After that, Forrest held odd jobs as a printer’s apprentice among other menial time-passers. His first step towards his big break came in an unusual circumstance. In early 1820, Forrest attended a lecture on the experiments of nitrous oxide. While under the gas’ influence, he started drunkenly articulating one of Richard III’s soliloquies. Philadelphia lawyer John Swift was so impressed with Forrest’s incantation, that he arranged an audition for the young boy at the Walnut Street Theatre.

Stop 1 – Walnut Street Theatre

America’s first star made his professional stage debut at America’s oldest theater, Walnut Street Theatre. Standing at the corner of 9th and Walnut since 1809 (just a few locks away from the Liberty Bell and Independence Hall), the Walnut was originally built as an equestrian circus. The first major theatrical production produced at the Walnut was The Rivals in 1812, with Thomas Jefferson and the Marquis de Lafayette reportedly in attendance. Since its opening, the Walnut has played host to some of America and Europe’s greatest stars, including Katherine Hepburn, Louis B. Mayer, Audrey Hepburn, Henry Fonda, Jane Fonda, Olivia de Havilland, Jack Lemmon, Gloria Swanson, the Marx Brothers, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, Jessica Tandy and Marlon Brando in the original pre-Broadway production of A Streetcar Named Desire and Sidney Poitier in the pre-Broadway engagement of A Raisin in the Sun, just to boast a handful of some of the most famous names of all time.

America’s first star made his professional stage debut at America’s oldest theater, Walnut Street Theatre. Standing at the corner of 9th and Walnut since 1809 (just a few locks away from the Liberty Bell and Independence Hall), the Walnut was originally built as an equestrian circus. The first major theatrical production produced at the Walnut was The Rivals in 1812, with Thomas Jefferson and the Marquis de Lafayette reportedly in attendance. Since its opening, the Walnut has played host to some of America and Europe’s greatest stars, including Katherine Hepburn, Louis B. Mayer, Audrey Hepburn, Henry Fonda, Jane Fonda, Olivia de Havilland, Jack Lemmon, Gloria Swanson, the Marx Brothers, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, Jessica Tandy and Marlon Brando in the original pre-Broadway production of A Streetcar Named Desire and Sidney Poitier in the pre-Broadway engagement of A Raisin in the Sun, just to boast a handful of some of the most famous names of all time.

The great British actor, Edmund Kean, invented the theatrical tradition of the curtain call at the Walnut. Today, this non-profit theater is the State Theatre of Pennsylvania and the most subscribed theater in the world, producing some of Philadelphia’s most popular live entertainment. It is the oldest continuously operating theater in the English-speaking language.

The Walnut is a mecca for Forrest enthusiasts, and for good reason. On November 27, 1820, at the age of 14, Edwin Forrest made his professional debut on America’s greatest stage at the time. Unknown in that moment in the role of Young Norval, he was simply billed as “a young man of Philadelphia” in John Holmes’ tragedy Douglas. Imagine being in the audience and seeing this scrappy kid cross the boards, not even aware that he would become the first American superstar.

The critic of The Aurora, a Philadelphia newspaper, wrote of his performance: “We were much surprised at the excellence of his elocution, his self-possession in speech and gesture, and a voice that, without straining, was of such volume and fine tenor as to carry every tone and articulation to the remotest corner of the theatre.” William Wood, then the manager of the Walnut, was less impressed with Forrest, telling the young teen that he lacked star quality and he would not be rehired for subsequent productions. Knowing that the great actors of the time were British born, like Edmund Kean, and catching Wood’s innuendo that British born equaled better reviews, Forrest, the son of a Scottish immigrant, began a bitter resentment and his own personal revolutionary war against British actors. It was a lifelong resentment that would haunt him up to the Astor Place Riots.

Today, audiences at the Walnut Street Theatre can snap their picture with Edwin Forrest in statue form. Adorned in a tunic and breastplate, the Edwin Forrest statue now in the lobby depicts Forrest as Shakespeare’s Coriolanus. "The Roman manliness of his face and figure, the haughty dignity of his carriage and the fire in his eye render his Coriolanus one of the most finished, striking and classical performances that was ever exhibited on the American stage," wrote James Rees about Forrest in 1874. The statue once belonged to Forrest. Never underestimate the ego of an actor who owns a gigantic marble statue of himself. Yes, you may notice that the statue bears a striking resemblance to another “man’s man,” Parks and Recreation’s Ron Swanson. Many people have noticed the uncanny mirror image, but the Walnut staff can assure you that it is Edwin Forrest, not Nick Offerman. The Walnut also has collected other Forrest memorabilia over the years, including a lock of his hair and props used by the actor. Legend has it that his ghost still haunts Walnut Street Theatre.

After he closed at the Walnut, Forrest joined a troop of actors and toured the country from Pittsburgh to New Orleans, finding great success and his star rising along the way. In December 1825, Forrest played Iago opposite Edmund Kean’s Othello. Forrest, playing against the types of Iagos in the past, played him lightheartedly and femininely. Iago's "Look to your wife. Observe her well with Cassio" was spoken in "a frank and easy fashion, suddenly changing to a hiss into Othello's ear" on the last words of the speech, according to Forrest biographer Richard Moody. The audience reacted with gasps to Forrest's delivery and Kean's startled expression. According to reporter, Kean said to Forrest afterwards: "In the name of God, where did you get that?" and Forrest replied that it was instinct. Kean, ever impressed with the new star, encouraged Forrest to move to London and perform on the grand stages of Europe, which would have been the equivalent of a promising actor moving to Hollywood today to find success.

Forrest declined, knowing his true calling was in the new upstart nation of the United States of America. He was bold and brassy, just like the new Americans of the time. He was known as the “working man’s” Shakespearean actor, a kind of blue-collar Macbeth, which fit in well with the rough and tumble rabble rousers of the day, who often would imitate his form in dives and barrooms. While English performers favored an elegant, intellectual style, Forrest pioneered an extroverted, heroic approach. This made him popular not only inside the theater but in pubs and on the streets as well. He was a cultural rebel, striking a blow against British tastes that echoed America's political rebellion against the Brits.

Forrest declined, knowing his true calling was in the new upstart nation of the United States of America. He was bold and brassy, just like the new Americans of the time. He was known as the “working man’s” Shakespearean actor, a kind of blue-collar Macbeth, which fit in well with the rough and tumble rabble rousers of the day, who often would imitate his form in dives and barrooms. While English performers favored an elegant, intellectual style, Forrest pioneered an extroverted, heroic approach. This made him popular not only inside the theater but in pubs and on the streets as well. He was a cultural rebel, striking a blow against British tastes that echoed America's political rebellion against the Brits.

At the age of 20, it was Forrest's turn to play Othello at the Chestnut Street Theatre, which once stood at 6th and Chestnut Streets. When he was 21, he was making $200 a night. Within the next few years, he was up to $500 a night, making him the highest paid actor in the world at his time.

Although he found himself in high demand, touring the fledgling nation and the stages of Europe, Philadelphia was Forrest’s home base, performing constantly at the Walnut, the Chestnut and the Academy of Music.

It was at this time that he used his well-earned money to found a playwriting contest. The plays were to be American written, and of course, there had to be a role for Forrest himself. The first play to win the contest was Metamora by John Augustus Stone in 1828. The winner the following year was The Gladiator by Robert Montgomery Bird. Other winning titles include Richard Penn Smith's Caius Marcus; two other plays by Robert Montgomery Bird: Oralloosa and The Broker of Bogota; and Robert T. Conrad's Jack Cade. Forrest is known now as a great Shakespearean actor as well as a supporter of emerging playwrights, as his contest helped get their plays produced.

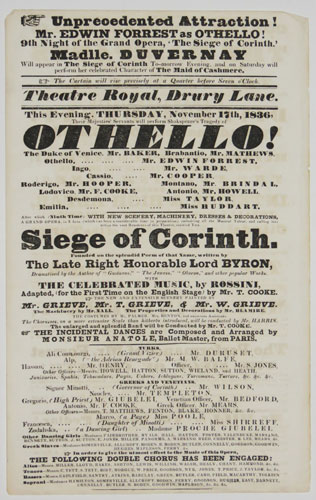

Forrest set sail for the English stage in September 1836, ready for his London debut of Spartacus in The Gladiator at the Drury Lane Theatre. He also performed for ten months the roles of Macbeth, Othello and King Lear. He was entertained by England’s superstars William Charles Macready and Charles Kemble. At an exclusive engagement at the end of the season in the West End’s Garrick club, he met a lovely 19 year old actress by the name of Catherine Sinclair. She was the daughter of a popular singer, John Sinclair. Now at the age of 31, he married Catherine Sinclair.

In 1938, Forrest was granted the highly unusual honor of delivering the main oration at a Democratic Convention on July 4, 1838. What was unusual was that the main orator was usually the President, in this case, Martin Van Buren. But politicians vied to have this superstar patriot on their side, and at 32 years old, he easily could have maneuvered into politics. It’s not as if we’ve never had actors in the White House before!

Stop 2 – The Forrest Theatre

If you’ve ever walked down the 1100 block of Walnut Street, you’ve passed the Forrest Theatre. You may have wondered who it was named after. Now you know!

Ground was broken for the "new" Forrest Theatre on September 1, 1927, and it was built at a cost of over $2 million dollars. Construction was completed in time for a May 1, 1928 opening. The new venue boasted many modern conveniences including wider seats in the orchestra, a smoking room for both men and ladies in the lower lounge and state of the art ventilation and electrical systems. The opening performance was The Red Robe, starring Walter Woolf and Evelyn Herbert. Although Forrest had not lived to perform on the Forrest's stage, the theater is named in his honor. Still a functioning theater owned by the Shubert Organization in New York (this is the last surviving Shubert Theatre outside of New York), the Forrest has been an important fixture in American theater history. Years ago, during the Golden age of Broadway, shows would have out-of-town tryouts at “Road Houses” in Philly, New Haven, Boston and Baltimore before heading to Broadway. This gave the creative team the chance to gauge audience response and tweak the shows before making their Broadway debuts. The Forrest was crucial for tryouts, and the Philadelphia critics were notoriously rough on incoming shows.

That’s a good thing though – without those reviews, many shows would have limped their way to Broadway and closed overnight. Instead, the shows were worked on in these tryout cities. Operations Manager Michael Romano was kind enough to give me a tour of the theater and provide for me a list of some of the famous shows that have passed under the proscenium. Some highlights include Funny Girl with a then unknown Barbra Streisand in 1964, Chicago with Gwen Verdon and Chita Rivera in 1975, Something For The Boys with Ethel Merman in 1944, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes with Carol Channing in 1949, Guys And Dolls in 1950, Porgy And Bess in 1936, Private Lives with Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton in 1983, Sammy Davis Jr. in Concert in 1967, The Women in 1936, and Stephen Sondheim’s ill-fated Anyone Can Whistle with Angela Lansbury in 1964 (they should have spent more time in Philly, Anyone Can Whistle only played nine performances on Broadway). Zero Mostel, of Fiddler on the Roof and A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum fame, collapsed on the stage of the Forrest in 1977 and died at Jefferson Hospital next door. Today the Forrest plays host to many touring shows in Philadelphia, including The Phantom of the Opera five times. Upcoming shows include Cats and the megahit Hamilton this summer.

Astor Place Riots

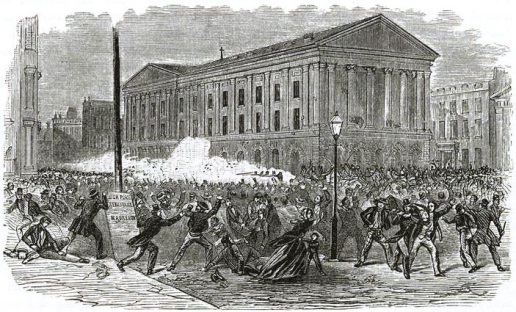

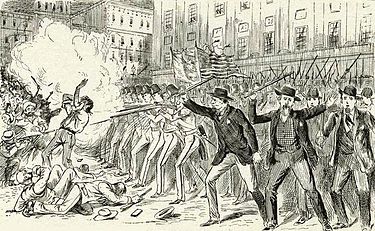

May 10, 1849 was a day that would live in infamy for Edwin Forrest. In mid-19th century America, theaters were gathering places for the masses and a place where their voices could be heard. They were entertainment and political centers. In New York City, fans would flock to see their favorite stars, as if they were modern day movie stars or sports heroes. Uptown at the Broadway Theatre, Edwin Forrest was appearing as Macbeth to awed, patriotic audiences. Downtown at the Astor Place Theatre, William Charles Macready, the greatest British actor of his day, and Forrest’s biggest rival, was also appearing as Macbeth. Forrest was the common people’s, or “Forrester’s” favorite, a truly organic American-born superstar. Macready’s represented the upper class that supported the British actor. Wounds from the American Revolution were still festering, and the nervous tension between the two actors and their fans was palpable all over Manhattan. The “Forresters” decided to play a nasty trick on Macready. For the May 7th show, they bought nearly all the tickets to his performance of Macbeth, simply to make the British actor feel unwelcome in the states by heckling him with cries of “shame, shame!” and “down with the codfish aristocracy!”

Words weren’t apparently enough to dissuade the actor, the show must go on! Soon the Forresters forced the show to a grinding halt by throwing garbage, rotten eggs, oyster shells, ripped up seats and fetid food at Macready. Meanwhile, uptown at the Broadway, the audience rose and cheered when Forrest spoke Macbeth's line "What rhubarb, senna or what purgative drug will scour these English hence?" The new Whig mayor of New York, Caleb S. Woodhull, sensing impending disaster, ordered a militia stationed in Washington Square at the May 10th performance at the Astor. Sure enough, the same thing happened. 10,000 people from both sides of the spectrum met at the Astor to protest or counter protest.

The crowd was whipped into a frenzy, and the police chief cried out to quell the crowd, but nothing could be done to stop the angry rabble. Soon enough, the militia were firing guns into the crowd to get them to disperse. All hell broke loose. Within minutes, 23 civilians were struck dead and countless injured. It was the first time an American militia fired on its own citizens in this country. Between this event and a nasty high profile divorce from Catherine Sinclair in 1851 in which both parties cried infidelity, Forrest’s personal life was falling apart. In 1865, he, along with the rest of the nation, mourned his personal friend, Abraham Lincoln, who was shot by actor John Wilkes Booth at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C. on April 15, 1865. Forrest had been personal buddies with the slain President, and Lincoln found a favorite actor in Forrest. Edwin Forrest and Junius Brutus Booth Sr., the patriarch of the Booth family, named his son Edwin after Forrest. And in true form, Edwin Booth became one of the most popular actors of his day, too. The pit of despair Forrest must have felt when his old friend’s name became synonymous with assassination must have been unfathomable, and certainly Forrest’s career as an actor suffered as his industry became looked down upon because of this heinous act of an actor.

Stop 3 – Freedom Theatre/Forrest House

Edwin Forrest continued his acting career, despite the scandal and personal demons swirling around him. In 1855, Forrest purchased a brownstone mansion at 1346 North Broad Street in Philadelphia. Three and a half stories tall and built in the Italianate architectural style, the house included Forrest’s extensive library and a courtyard with a fountain. A gallery attached to the house provided space for Forrest’s art collection as well as a private theater with a small stage. In later years, it served as the Philadelphia School of Design for Women, until it expanded and ultimately became the New Freedom Theatre, serving the city’s African-American community and training actors such as Leslie Odom, Jr., who would go onto star in Broadway’s Hamilton.

Stop 4 – St. Paul’s Episcopal Church and Cemetery

On the night of March 25, 1871, Forrest appeared in Boston at the Globe Theatre, as Lear. He played this part six times, and was announced to also appear as Richelieu and Virginius. But then he developed pneumonia. He struggled through a performance, and it was reported that “rare bursts of eloquence lighted the gloom, but he labored piteously against the disease.” When offered medications, Forrest waved them away with the words, “If I die, I will still be my royal self.”

That was his last appearance as an actor. After that, the infirm Forrest limited himself to dramatic Shakespearian readings. Forrest died in his sleep in December of 1872 at age 66 at his home on North Broad Street.

In his will, Forrest left much of his estate for the formation and maintenance of the Edwin Forrest Home, a residence where elderly actors could live and receive medical attention for no cost. The home initially opened at Springbrook, Forrest’s country residence in the Holmesburg area of North Philadelphia, in 1876. In the 1920s, the home moved briefly to a mansion in Torresdale before relocating to a facility at 4849 Parkside Avenue near Fairmount Park in 1928. The home remained in existence at that location until 1986 when it merged with the Lillian Booth Actors’ Home of the Actors’ Fund of America in Englewood, New Jersey. A wing at the Lillian Booth Home is named in honor of Edwin Forrest. Forrest was laid to rest in a family vault in St. Paul’s Episcopal Church on South 3rd Street near Walnut Street.

Forrest’s larger than life legacy remains in the hearts of Philadelphia’s theater community. “Forrest was a big, over-the-top man who was representative of the tempest of his times,” said writer/actor Will Stutts. “He was America’s first native-born actor, and a bounder who fell madly in love with a woman who was unfaithful.” A group of admirers gathers at Forrest’s tomb in Philadelphia on his birthday every March 9th to lay a wreath and drink a toast to his memory. Others observe a provision of Forrest’s will by gathering to read the Declaration of Independence aloud each July Fourth.

Photo Credits:

Walnut Street Theatre Photos: Credit to Wendy Furman.

Forrest Theater, Forrest Home and Grave Photos: Credit to Andrew Terranova.