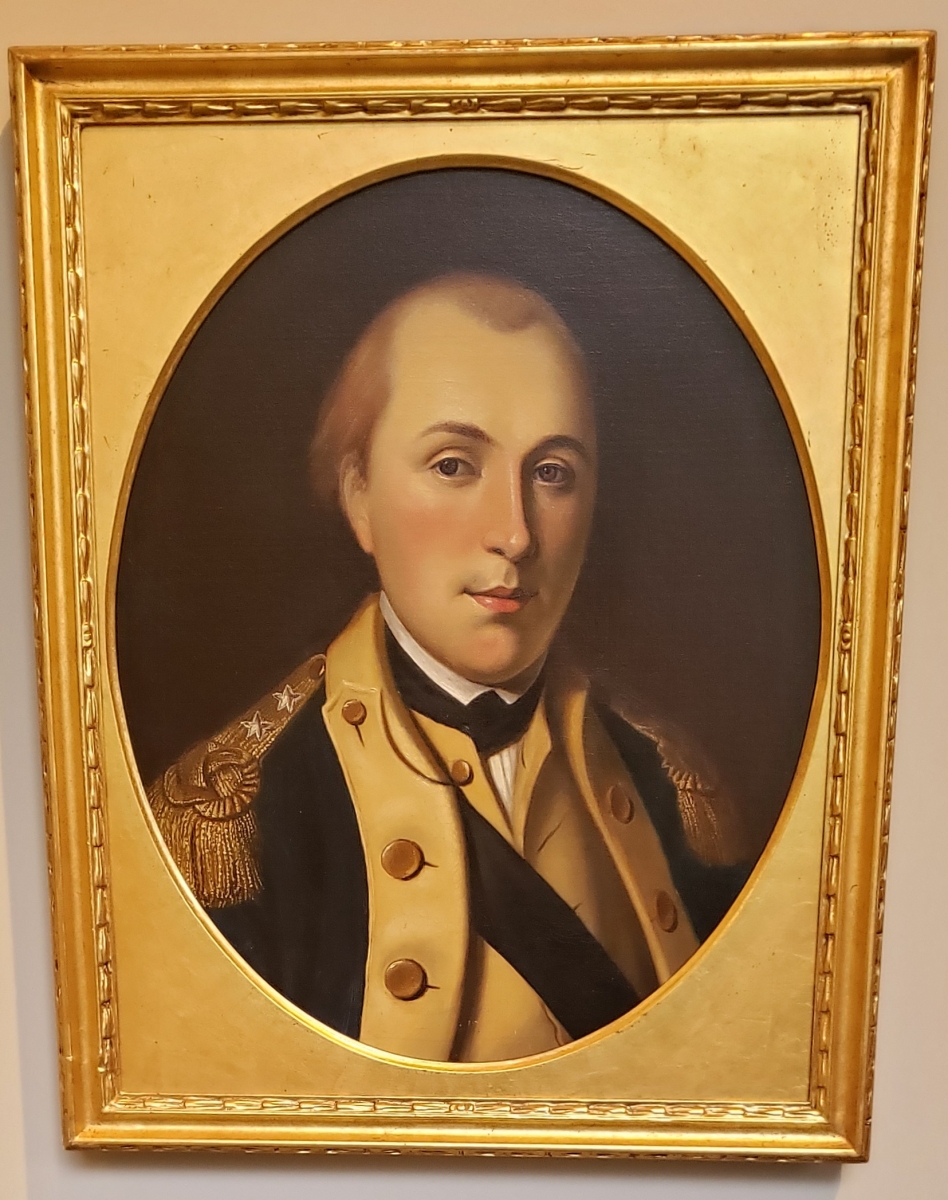

Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette - One of America's Founding Fathers

Related Posts

- Buy Tickets for The Constitutional Walking Tour of Philadelphia – See 20+ Sites on a Primary Overview of Independence Park, including the Liberty Bell and Independence Hall

- Independence Hall

- Valley Forge National Historical Park

- New Hall Military Museum

- Museum of the American Revolution

Birth: September 6, 1757

Death: May 20, 1834 (age 76)

Colony: N/A

Occupation: General

Significance: Served as Major General in the Continental Army (1777-1783); and authored the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (1789)

Early Life and Education

Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette was a Founding Father of the United States. Lafayette was born to a fabulously wealthy aristocratic family in Auvergne, France. Though frequently referred to by the name Marquis de Lafayette or simply Lafayette in the United States, the Marquis de Lafayette was not his name, but rather a title of nobility that Lafayette inherited as a small child when his father died while fighting in the War of Polish Succession.

When Lafayette was 11 years old, he moved to Paris to live with his mother in Luxembourg Palace. Lafayette was educated at the University of Paris and trained to be a Musketeer. At the age of 12, Lafayette’s mother died, leaving him an enormous fortune. In 1771, when Lafayette was just 14 years old, he was commissioned into the French Army as a Musketeer, but was allowed to continue his studies. Lafayette was placed in an arranged marriage when he was just 14 to the 12 year old Marie Adrienne Francoise, another child of a wealthy French aristocrat. After a period of courtship, Lafayette and Marie were officially married two years later in 1774 when they were 16 and 14 respectively.

After his engagement, Lafayette moved to Versailles to live with his wife and his father in law and continued his education at the Academy of Versailles. After the completion of his studies, Lafayette was commissioned into the French Army as a lieutenant.

The American Revolution

When Lafayette heard of the American Revolution, he was inspired by the idea of people fighting for their liberties and took great interest in the conflict. His view of the American Revolution was influenced by the fact that his father had died fighting the British.

Upon turning 18, Lafayette was granted the military title of Captain in the Dragoons (a class of mounted infantry). When Lafayette discovered that King Louis XVI was covertly sending arms and soldiers to America to support the Americans, Lafayette demanded to be among the officers sent to America. However, when the British uncovered the scheme and threatened war in retaliation, the French canceled their plans. But Lafayette was undeterred and decided to head to America on his own.

Lafayette arrived in Philadelphia in July of 1777 at the age of just 19 years old, barely able to speak any English and without any previous combat experience. However, his world class military education, his connections in France, and his offer to serve without pay made Lafayette very appealing to the Continental Congress which commissioned him as a Major General into the Continental Army.

A few weeks later, Lafayette had dinner with George Washington while he was in Philadelphia to brief the Continental Congress. Washington was impressed with the young Lafayette and took him on to become a member of his staff. Shortly after joining Washington, Lafayette saw his first combat in the Battle of Brandywine which was a crushing loss for Washington and the Continental Army. Lafayette was shot in the leg during the battle, but nonetheless refused to abandon his post or receive treatment until he carried out his order and his men had safely retreated. After the Battle of Brandywine, he received an official citation from Washington for “bravery and military ardour”, and Washington recommended that Lafayette be given command of a division.

Lafayette then spent the winter with Washington and his army at Valley Forge, enduring the difficult conditions and deepening his friendship with Washington who would end up becoming a sort of surrogate father figure to Lafayette.

Lafayette continued to distinguish himself on the battlefield as the Revolutionary War progressed, but then in 1779, Lafayette was given a different sort of mission as Lafayette was sent home to France to assist with securing more French troops to support the American Revolution. Initially imprisoned by King Louis XVI for disobeying orders about traveling to America, Lafayette was released after just eight days and was allowed to make his case for increased American assistance to King Louis XVI. While back in Paris, Lafayette also fathered his first son, George Washington Lafayette, named after the American General. Eventually, Lafayette was instrumental in securing 6,000 French soldiers to assist the American Revolutionary War effort. Lafayette then returned to America in 1780, commanding the French troops who had accompanied him.

Lafayette and his men played a critical role in the Battle of Yorktown, where he held back the British soldiers until Washington and his men had arrived. Washington and Lafayette then commenced a siege that led to the surrender of British General Cornwallis that ended large scale fighting in the American Revolution.

The French Revolution

After the American Revolution came to a conclusion, Lafayette traveled back France in 1782. Officially named an advisor to America’s diplomats abroad, Lafayette coordinated communications regarding the treaty to end the Revolutionary War between Benjamin Franklin in France, John Jay in Spain, and John Adams in the Netherlands. Lafayette also assisted America in negotiating its first trade agreements and took part in the Treaty of Paris negotiations.

In France, Lafayette was hailed a hero and promoted to a senior rank in the French Military and was appointed by King Louis XVI to the Assembly of Notables, which was formed in response to France’s economic issues that stemmed in part from the enormous sum which the French had loaned the United States to fight the Revolutionary War.

As the situation in France degraded further and began to slip toward Revolution, Lafayette found himself in an awkward position as he possessed extraordinary wealth and enjoyed close ties with the royal family, while at the same time, Lafayette believed many of the grievances that led to the French Revolution were legitimate and closely mirrored the ideals he had traveled to America to fight for and risk his life. In 1789, Lafayette helped author the “Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen” which was based in part upon The Declaration of Independence, and Thomas Jefferson himself actually assisted Lafayette in writing it. Designed as a basic charter of human liberties and the principles of the French Revolution, it was meant to serve as guiding principles in a French transition to a Constitutional Republic.

As the French Revolution proceeded, Lafayette found himself in positions of increasing power since he was one of the few figures who had the trust of both the monarchy and many of the revolutionaries. As the commander in chief of a newly formed French National Guard, Lafayette tried to keep France from spiraling into chaos. In the end though, the delicate balancing act that required Lafayette to remain favorable to two warring factions was impossible. As Maximilien de Robespierre was coming to power, he accused Lafayette of treason, and Lafayette left France, heading north into Austrian Netherlands (Belgium today).

In the Austrian Netherlands, Lafayette was arrested and accused as helping to ferment the rebellion that lead to the execution of the King and Queen of France. Lafayette remained imprisoned for over five years, from 1792 to 1797. The friends Lafayette had made in America, especially Washington who was President of the United States at this time, were a major reason for Lafayette’s release.

As Napoleon began to take hold of power in France in 1799, he allowed Lafayette to return to France on the condition that he avoid politics and retire from public life. Lafayette and his family, who had their estate and fortune confiscated by the French Government, returned to France impoverished, and Lafayette began to work as a farmer. As Napoleon attempted to consolidate his power, he viewed Lafayette as a possibly valuable ally and offered to make Lafayette Minister to the United States. Lafayette believed Napoleon’s rule was unconstitutional however, and refused to participate in an undemocratic French government. Little changed for Lafayette when Napoleon was overthrown in 1814, and the monarchy of France was restored, as France had just exchanged one undemocratic government for another.

Tour of the United States

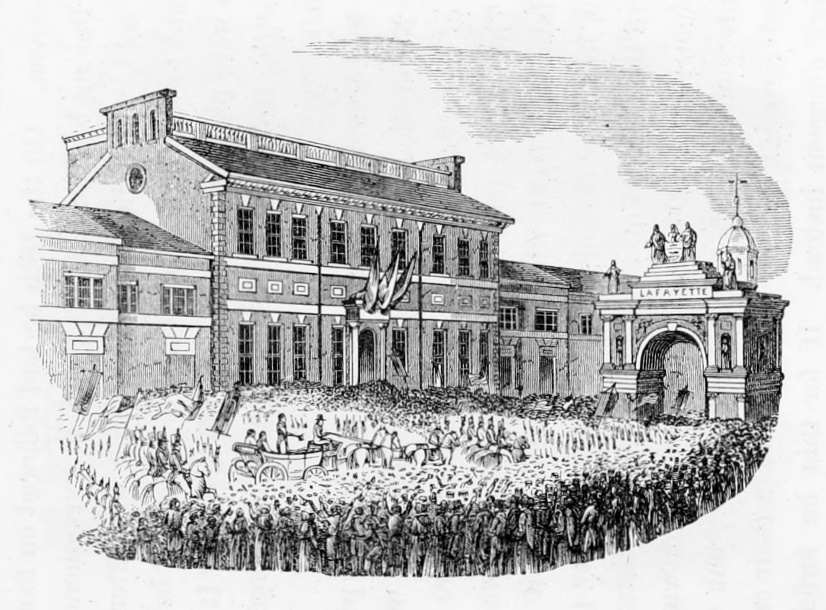

After living a relatively quiet life for a quarter of a century, in 1824, President James Monroe invited Lafayette to take a tour of America in anticipation of the America’s 50th anniversary. Now widowed and an elderly man of 67, Lafayette returned to the country he helped to found, and he was welcomed as a hero. Lafayette’s tour lasted 16 months as he visited all 24 states that comprised the United States at the time. Everywhere he went, Lafayette was treated to elaborate celebrations, but perhaps none were bigger than in Philadelphia.

In preparation for Lafayette’s visit, Independence Hall was refurbished to serve as the location for a grand celebration of Lafayette. There were also over a dozen temporary Triumphal Arches that were constructed to line the path Lafayette would take into the city with the final Arch standing in front of Independence Hall. Once in front of Independence Hall, Lafayette gave a speech in front of Independence Hall which included the following passage:

“My entrance through this fair and great city amidst the most solemn and affecting recollections, and under all the circumstances of a welcome which no expression could adequately acknowledge, has excited emotions in my heart in which are mingled the feeling of nearly fifty years.

Here within these sacred walls, by a council of wise and devoted patriots, and in a style worthy of the deed itself, was boldly declared the independence of these vast United States which, while it anticipated the independence- and, I hope, the republican independence of the whole American hemisphere- has begun for the civilized world the era of a new and of the only true social order founded on the inalienable rights of man, the practicability and advantages of which are every day admirable demonstrated by the happiness and prosperity of your of your populous city.”

It was during Lafayette’s visit to Philadelphia that the old Pennsylvania State House began to be called the “Hall of Independence” which eventually became “Independence Hall”. The visit of Lafayette is a major reason why Independence Hall was preserved and became a tourist site that attracts visitors from around the world. Because of its importance to the founding of the United States, Independence Hall is a United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage Site.

Final Years

Lafayette returned to France in 1825 to a new King, Charles X. Whether it was his inspirational trip to America, or the news that King Charles X was further destroying what little democracy remained in France, Lafayette returned to France reinvigorated to fight for the rights of French citizens. Lafayette was an outspoken critic of Charles X and ran for and won a seat on the French Chamber of Deputies. Lafayette spoke out against the policies of Charles X and advocated for an American-style representative government. After Charles X dissolved the Chamber of Deputies in 1830, riots broke out in the streets and Lafayette was once again looked to as a leader.

Lafayette led protesters to a victory over Royal Guards which led to Charles X abdicating the throne. Lafayette was restored to the commander of the Parisian National Guard and helped the transition toward a new King, Louis Philippe I, who had promised democratic reforms. But once installed, King Louis Philippe went back on his word and refused to implement the promised reforms. Lafayette remained an outspoken critic of the monarchy until his death in 1834. Although he played a major role in bringing a constitutional republic to the United States, he died before seeing a constitutional republic realized in his native country of France.

Lafayette in Philadelphia

When Lafayette first arrived in Philadelphia in 1777, it was at Independence Hall where he was commissioned an officer in the Continental Army. Lafayette traveled back to Philadelphia frequently during the American Revolutionary War. Years later in 1824, Lafayette once again came to Philadelphia to a large celebration where he was honored in front Independence Hall.

Today in Philadelphia you can visit the New Hall Military Museum and the Museum of the American Revolution, both of which house artifacts from the American Revolutionary War and pay tribute to the soldiers such as Lafayette who fought for American independence. Another tribute in Philadelphia to those who fought in the American Revolution is the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, located in Washington Square Park, which is just steps off of the tour. Independence Hall, New Hall Military Museum and the Museum of the American Revolution are stops on The Constitutional Walking Tour!