Related Posts

- Buy Tickets for The Constitutional Walking Tour of Philadelphia – See 20+ Sites on a Primary Overview of Independence Park, including the Liberty Bell and Independence Hall

- Alexander Hamilton: The Constitutional Clashes That Shaped a Nation Exhibit

- Independence Hall

- Signers' Garden

- Signers' Walk

- Second Continental Congress

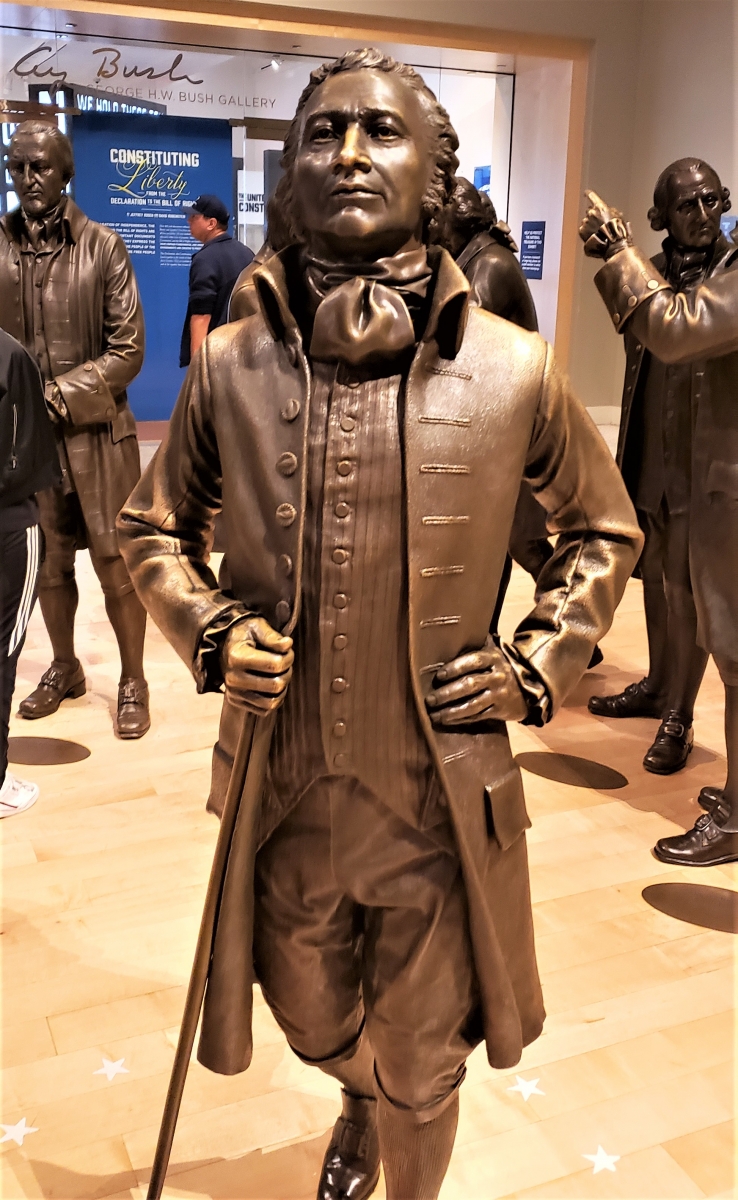

- Constitutional Convention

- Congress Hall

- National Constitution Center

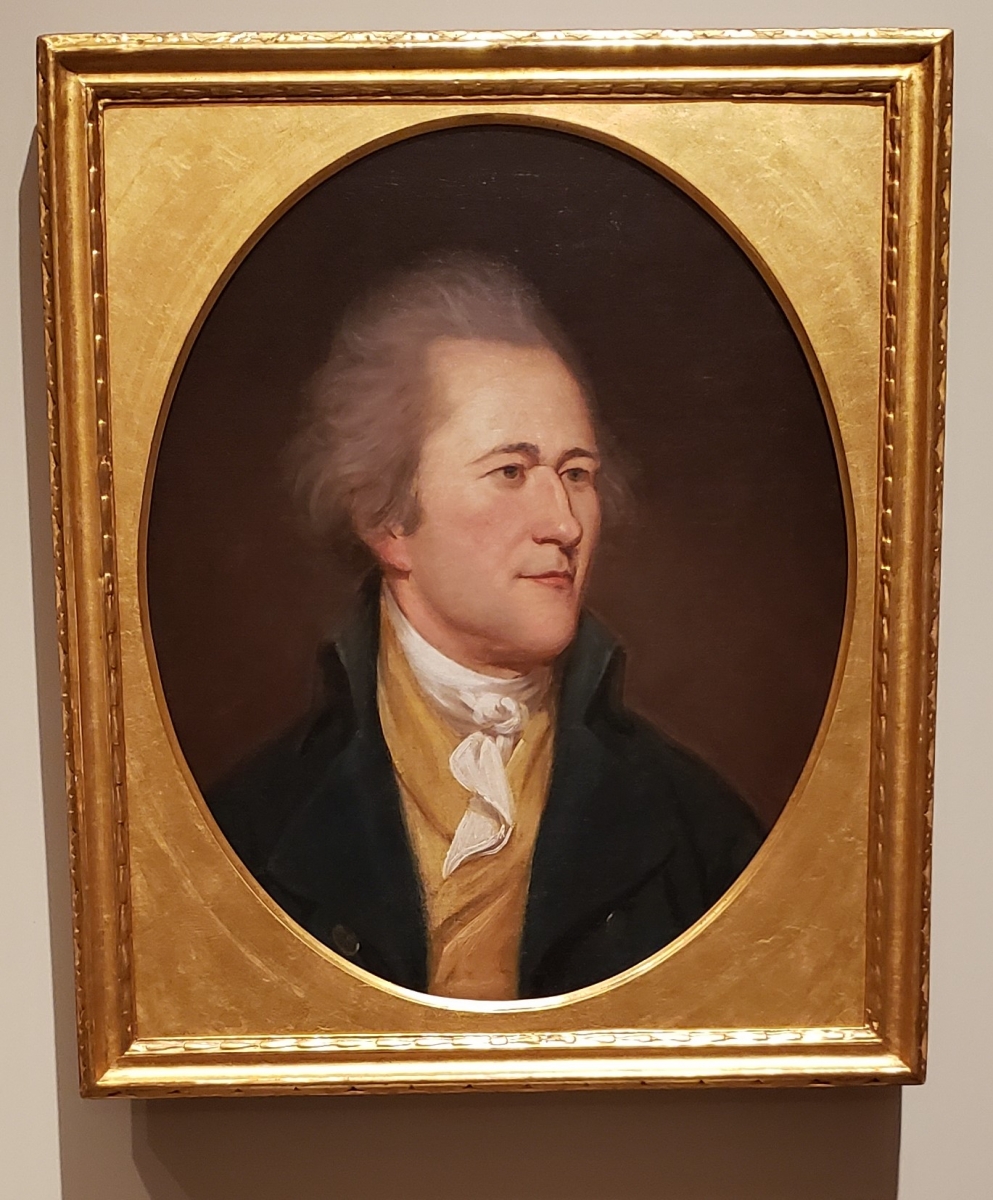

- Alexander Hamilton in Philadelphia

- The First Bank: Centerpiece of Hamilton’s “Cabinet Battle #1”

Birth: January 11, 1757

Death: July 12, 1804 (age 49)

Colony: New York

Occupation: Lawyer, Politician, Soldier

Significance: Signed the United States Constitution (at the age of 30); and served as first United States Secretary of the Treasury (1789-1795)

The American Revolution

The Pennsylvania Mutiny

Creation and Ratification of the Constitution of the United States

Federalist Papers

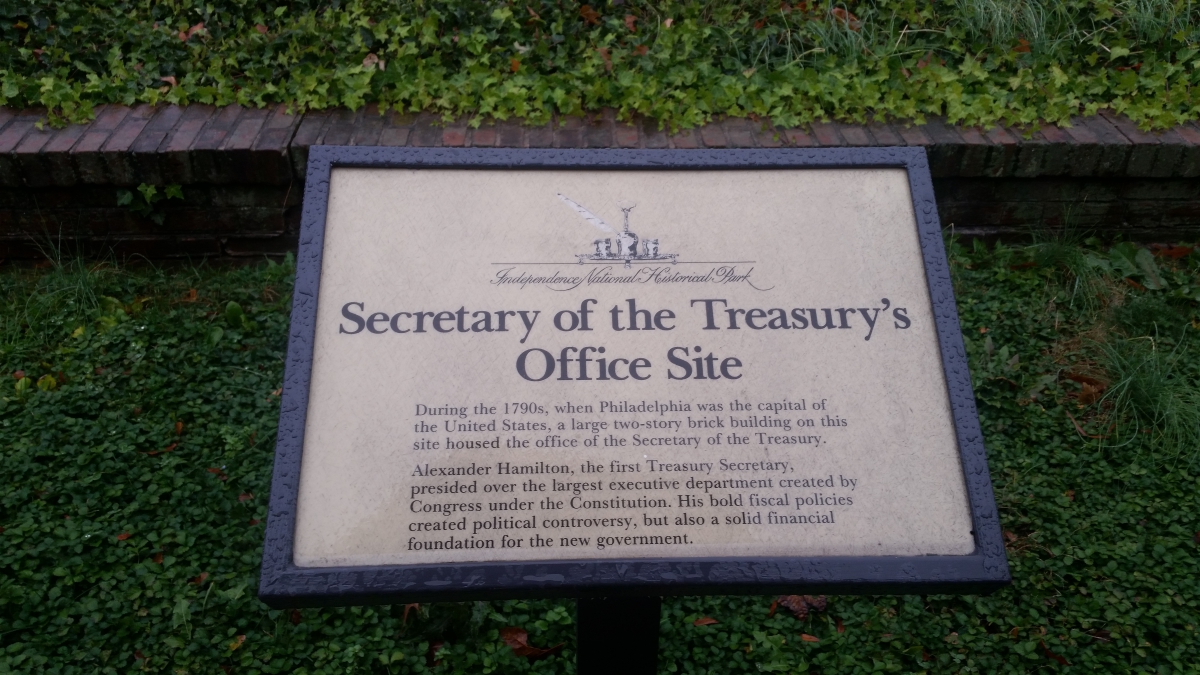

Secretary of the Treasury

Arguably, Hamilton’s greatest political victory was the establishment of a Federal banking system. Hamilton's banking system was criticized by small government focused Southern agrarians such as James Madison and Thomas Jefferson, and sparked the nation’s first great Constitutional debate. Despite the political controversy, Hamilton eventually convinced both George Washington and Congress to support his plan.

The resulting First Bank of the United States became one of the most important financial institutions in the world for a period of time. It was also during his time as Secretary of the Treasury that Hamilton convinced the U.S. Congress to pass the Coinage Act of 1792 which resulted in the creation of the United States Mint.

Hamilton's controversial policies as Secretary of the Treasury were actually a major reason for the creation of political parties in America. Those who supported Hamilton's policies became known as Federalists, and those that opposed them became known as Democratic-Republicans. In general, the Federalists were centered more in the North and believed in a stronger centralized federal government, whereas the Democratic-Republicans were centered more in the South and championed state's rights over a strong central government.

Hamilton resigned as Secretary of the Treasury in early 1795 in order to be closer to his wife Elizabeth who had just suffered a miscarriage.

Hamilton's Final Years and Death

After leaving President Washington's Cabinet, Hamilton returned to New York City to be with his wife and began practicing law. Although away from the Federal government, Hamilton remained deeply involved in its proceedings. Hamilton even tried to scheme for a way for the the Federalists to retain power in 1796, but to prevent John Adams from becoming president. Adams and Hamilton had a difficult relationship, as they were political allies and leaders of the Federalist party but had a mutual personal dislike of one another. Hamilton's plan failed however, Adams became President and did his best to shut out Hamilton from power as payback for the scheme.

However, when John Adams and his presidency became entangled in a Quasi-War with France, Adams did name Hamilton a Major General in the United States Army. This was done largely out of Adam's respect for George Washington, since Adams had convinced Washington to come out of retirement to lead the Army again, and Washington requested Hamilton as one of his Generals.

Hamilton served as Inspector General of the United States Army from 1798-1800. With General Washington in poor health and largely remaining in Mount Vernon in Virginia, Hamilton was for all intents and purposes, the leader of the Army. After Washington's death in 1799, Hamilton was the most senior officer in the United States Army. Once the situation with France was resolved however, Adams no longer had a need for a standing army, and Hamilton was removed from his position.

In the election of 1800, Alexander Hamilton again found himself in a difficult position. Hamilton's main concern was the Federalist party remaining in power, but Hamilton had such intense dislike of John Adams (a fellow Federalist and the sitting President of the United States,) that Hamilton orchestrated a scheme that would cause John Adams to lose the presidency, while ensuring that another Federalist would take his place. Once again however, Hamilton's plans failed and this time they backfired.

Hamilton's actions against Adams only managed to split the party which cleared the way for the Democratic Republicans to grab power for themselves. The Democratic Republicans had issues of their own, however as both Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr had tied in votes for the Presidency, and it was unclear who would become President. Hamilton once again became involved to his own detriment. Though politically opposed to both Jefferson and Burr, Hamilton spoke highly of Jefferson's character while he referred to Burr as a "mischievous enemy." This led to some Federalist throwing their support to Jefferson to break the deadlock, and making Jefferson America's third president.

These types of political schemes and backroom deals are big part of why Hamilton is such a fascinating historical figure. The political intrigue that surrounded Hamilton's life is a big reason why "Hamilton - The Musical" has become one of the biggest hits in the history of Broadway. But while they make for a fascinating story, these types of deals rarely worked out in Hamilton's own life. But no scheme worked out worse for Hamilton than his attempted character assassination of Aaron Burr.

This attack on Burr's character made during the 1800 election was not be the last Hamilton made. A few years later, as Burr ran for Governor of New York, Hamilton again attacked his character. This eventually led to an ever-escalating feud in which Hamilton refused to apologize and eventually led to their famous duel.

On July 11, 1804, in a small New Jersey town across the Hudson River from New York City named Weekawken, Hamilton met Burr for a duel. Before the duel, Hamilton wrote that he felt that dueling went against his moral code, but that he could not in good conscience apologize to Burr, as he felt everything he said was true. Hamilton also wrote that he intended to "throw his shot" which was when a dueler refused to actually shoot at the person he was dueling. In duels, it was not uncommon for both parties to "throw their shot," and these duels in which no one was actually shot at, represented a type of way to defend one's honor without harming another man. But Burr was apparently uninterested in throwing his shot in return. Both men fired, but whereas Hamilton shot the tree above Burr's head, Burr fatally wounded Hamilton. It is still unknown today who fired first and exactly what their intentions were, but Hamilton was paralyzed by his wounds and after over a day of terrible pain, Hamilton succumbed to his wounds on July 12, 1804 in Manhattan.

Alexander Hamilton in Philadelphia

Hamilton spent many years in Philadelphia while the city served as the capital of the United States. Hamilton first lived in Philadelphia while a member of the Continental Congress at the end of the Revolutionary War, during this time Hamilton worked at Independence Hall. Hamilton returned to Independence Hall in 1787 to help draft and sign the United States Constitution. While working on the Constitution, Hamilton stayed in a boarding house operated by Miss Dailey, located at the corner of 3rd and Market Streets. Hamilton again lived in Philadelphia while he served as Secretary of Treasury under George Washington. During this time Hamilton created The First Bank of the United States and the United States Mint. The First Bank still stands, and while the original mint is no longer standing, there is a current United States Mint still located in Philadelphia today. While none of the residences Hamilton lived in during his many years in Philadelphia still stand today, a property on the 200 block of Walnut Street has a large plaque commemorating the location of where Alexander Hamilton once lived with his wife Elizabeth.